Rumi: “The body is a device to calculate / the astronomy of the spirit. / Look through that astrolabe / and become oceanic.”

Today we feature 13th-century Sufi poet Jalal al-Din Rumi, one of the most popular spiritual poets in the world

How did an ancient Persian poet known simply as Rumi become one of the best-selling poets in modern America? How did his words make their way into wedding vows and onto t-shirts, tea towels, and bumper stickers?

Here are some examples of Rumi’s quotes that you might recognize:

Lovers don't finally meet somewhere. They're in each other all along.

Let the beauty we love be what we do.

There are hundreds of ways to kneel and kiss the ground.

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I'll meet you there.

Before we dive into Rumi’s poetry, today’s Poetry Buds is going to become a miniature Time Machine, turning your phone screen (or computer monitor) into a sleuthing portal to the past. Who was Rumi? How did his words reach us? How did he become so popular?

First set of Time Machine coordinates: 1976. America. Coleman Barks.

It is afternoon. Poet & professor Coleman Barks is at a writing conference held by the famous poet Robert Bly. Bly asks the attendees to rewrite literal translations of Rumi’s poems into free verse—as a fun “afternoon writing exercise.” It turns out that it is fun; Barks enjoys it immensely.

Before he leaves, Bly hands Barks a book of translations of Rumi’s and says, “These poems need to be released from their cages.” 1

Barks continues the exercise of “releasing” the poems into free verse when he returns home. According to Barks, it was “fascinating to me and a sublime relaxation. I would go to the Bluebird Café after teaching three classes and relax by reworking this poetry. I did it for about seven years before I even thought of publishing.” 2

Second set of coordinates: 1995. America. Brad Gooch.

It is Christmas. Brad Gooch—poet, novelist, and biographer—is about to get the same Christmas present three separate times from three separate people.

It is The Essential Rumi, a book written by Coleman Barks, and released that year. It is popular right away, and will go on to sell hundreds of thousands of copies.

Gooch, a multi-hyphenate writer, had just published a biography of Frank O’Hara. He will go on to write more literary and artistic biographies, including those of Flannery O’Connor, Keith Haring, and, eventually—the poetic phenomenon, Rumi.

Third set of coordinates: 1207. Afghanistan. Rumi.

It is September 30 and a boy named Muhammad is born in Balkh, Afghanistan.

He won’t be called Rumi until years later (if at all, in his lifetime.) Why? “Rumi” means “from Roman Anatolia” and doesn’t apply until his family, fleeing the invading Mongols, makes the grueling 2,500-mile journey from Afghanistan to Konya, Turkey. His father, who is a religious scholar and preacher, has been offered a job there. Rumi is probably just under ten when the family sets out. 3

This 6-minute TED-Ed video provides a beautiful illustrated version of Rumi’s life and work, including the journey that his family undertook when he was a boy:

Fourth set of coordinates: 1244. Turkey. Shams of Tabriz.

Rumi is 37 now and still living in his new home of Konya. He is established as a respected scholar and preacher. He has inherited both his father’s work and followers.

Although he has had some mystical experiences (at the age of five he told his father he saw an angel), he is not currently on a mystical path.

One day, a wandering mystic named Shams of Tabriz comes to town, and everything changes.

“The two of them have this electric friendship for three years,” says biographer Brad Gooch in this BBC article. The men seclude themselves for months at a time. They are something not quite categorizable—teacher and student, yes, but also equals; friends, but with a powerful love that infuses the friendship; mystics, who are not bound by bodies, who inhabit some larger state of being, who are “oceanic.”

(One of my favorite lines by Rumi is: “The body is a device to calculate the astronomy of the spirit. Look through that astrolabe and become oceanic.” 4 In a similar vein, there is a popular quotation from Rumi that sometimes adorns merchandise: “You are not a drop in the ocean. You are the entire ocean in a drop.” I can’t verify this second quote, however, and I doubt it is completely accurate. Rumi is more likely to have said that a person is both—both a drop and an ocean, both a mortal human and a soul that is connected to the divine.)

This transcendent friendship changes the trajectory of Rumi’s spiritual path and becomes the basis for much of his poetry; themes of union and separation permeate his work. Friendship itself becomes both a container and a metaphor for spiritual experience.

One day, Shams disappears, never to be seen again. (There is conjecture that he was murdered. Listen to this podcast or read Gooch’s biography to get a feel for the complex dynamics in Rumi’s community, family, and culture.)

Rumi spends the remaining decades of his life as a mystic, poet, and teacher in the Sufi tradition. (Sufis are the group of mystics that that are connected to the dancing & spinning “whirling dervishes.”)

Most of his poetry is spoken aloud while in states of spontaneous ecstatic inspiration. His followers write these utterances down and preserve them.

Fifth set of coordinates: Present day. Turkey. A sculpture.

There is a small memorial on the spot where Rumi and Shamz met—a metal sculpture on the busy streets of modern-day Konya called “Meracel Bahrain,” which translates to “the meeting of two seas.” 5

It looks a bit like a flame—or maybe cupped hands—or a tulip with two petals that twist up & rise around an invisible flame. Or maybe like vertical waves from two seas.

A contemplation of all possible Time Machine coordinates:

So many moments both shaped Rumi’s poetry and preserved it—and brought it to modern readers.

What if the Mongols had not caused Rumi’s family to flee? What if Shamz had wandered into a different town? What if Rumi’s students had not written down his spoken poetry with such care? What if his poetry had been lost in the ensuing centuries?

What if Coleman Barks had not gone to that writing conference?

In this podcast, Brad Gooch traces some of the lineage of cultural discovery of Rumi by the Western world:

“…then at a certain point, different Europeans come across his poetry, usually in Istanbul. And then the German romantic poets pick up on Rumi, like Goethe. And the America transcendentalists, like Emerson, pick up on Rumi. And then the English Orientalists do. And I mentioned [earlier in the podcast] the American New age movement in the 1990s...”

As Gooch points out, Barks’ translations of Rumi’s poetry arrive at a time when certain spiritual trends aligned with the themes in the poems.

In that BBC article referenced earlier (which is called, “Why is Rumi the best-selling poet in the US?”) Gooch also says:

“He’s a poet of joy and of love,” says Gooch. “His work comes out of dealing with the separation from Shams and from love and the source of creation, and out of facing death. Rumi’s message cuts through and communicates. I saw a bumper sticker once, with a line from Rumi: “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing there is a field. I'll meet you there.”

Thank you for boarding the Time Machine with me! And now we return to our regular format.

There have been many translators of Rumi’s work, but I’ll use the translations of Coleman Barks in this post since he was so pivotal in Rumi’s recent popularity.

In his TEDx talk, Barks jokes: “People ask me how I got involved with the poetry of Rumi. How does a Presbyterian from Chattanooga [he pauses and chuckles here] get involved with the greatest poet of Islam in the 13th century?”

We know about the writing exercise and the meeting with Bly already. The TEDx talk unpacks even more connections. But here are a few of the commonalities that Barks and Rumi share:

Rumi was a Sufi. Barks has studied Sufism for many decades. Rumi had Shamz. Barks studied for many years with a Sufi teacher named Bawa Muhayadeen, who was originally from Sri Lanka, but lived in Philadelphia.

Their lives both have blends of the scholarly and the spiritual.

Also, Barks taps into a kind of spiritual experience as he writes. In this interview, he describes it like this: “Well, it's a little mysterious. I go into a kind of a trance, reading the poem in its scholarly translation, and try to…. I try to feel what spiritual information is trying to come through Rumi's images and then I try to put that into an American free-verse poem in the tradition of Walt Whitman and many others...” 6

“The Guest House” is probably one of Rumi’s most circulated poems, and is often shared in personal growth and mindfulness circles. It starts like this: “This being human is a guest house. / Every morning a new arrival. / A joy, a depression, a meanness…”

Later in the poem, Rumi advises:

Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they’re a crowd of sorrows,

who violently sweep your house

empty of its furniture,

still, treat each guest honorably.

He may be clearing you out

for some new delight.

Read the full poem.

In “A Thirsty Fish,” we see some of the same themes from his time with Shams—that the desire for union with an other (a friend, God, the universe) can be bigger than the container for that desire. We also re-visit this idea that a single human being can contain something vast, like an ocean.

Somehow, in the “physics” of mysticism, we humans can be both a thirsty fish and the ocean the fish swims in. Here is a section of the poem:

I have a thirty fish in me that can never find enough of what it's thirsty for! Show me the way to the ocean! Break these half-measures, these small containers. All this fantasy and grief. Let my house be drowned in the wave that rose last night out of the courtyard hidden in the center of my chest.

Read the full poem in The Essential Rumi, by Coleman Barks with John Moyne, Castle Books/ Harper Collins, 1995.

A favorite poem of mine is “Each Note.” This section of the poem explores feelings of longing, giddiness, and alive-ness. It also explores the idea that we are containers—that an external spiritual force animates us—whether that be God, or God’s breath, or our own breath, or the wind, or our own singing. The images multiply, but the feeling is the same—a spiritual force travels through us and we should allow it:

God picks up the reed-flute world and blows.

Each note is a need coming through one of us,

a passion, a longing-pain.

Remember the lips

where the wind-breath originated,

and let your note be clear.

Don't try to end it.

Be your note.

I'll show you how it's enough.

Go up on the roof at night

in this city of the soul.

Let everyone climb on their roofs

and sing their notes!

Sing loud!

Read the full poem in The Essential Rumi, by Coleman Barks with John Moyne, Castle Books/ Harper Collins, 1995.

More, please

Here is the TED-Ed video about Rumi referenced in the post:

Coleman Barks’ TEDx Talk:

This short video is about the Whirling Dervishes of Sufism:

Find a Bill Moyers special here.

Read some excellent articles in The Marginalian: Rumi’s life in ancient manuscripts, a new book of translation, and an album inspired by the poetry of Rumi and others.

Some podcasts with Coleman Barks or Brad Gooch:

What about you? Have you heard of Rumi? Do you have a favorite poem?

See you tomorrow with another poet!

Jenny

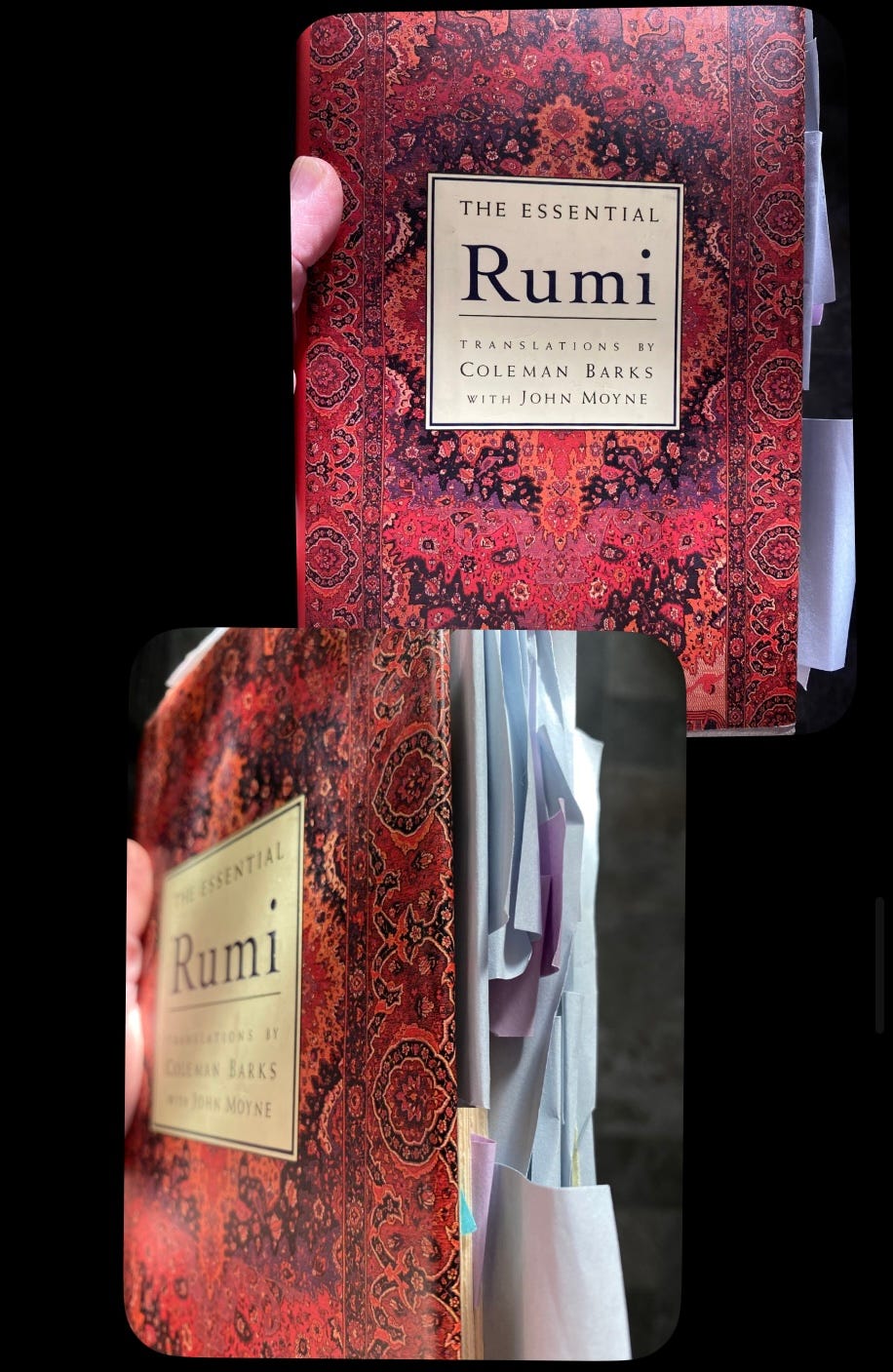

P.S. And just for fun—some photos I texted a friend when she mentioned Rumi. Had I heard of him? Yes, yes, I had.

The Essential Rumi, by Coleman Barks with John Moyne, Castle Books/ Harper Collins, 1995.

The Essential Rumi, by Coleman Barks with John Moyne, Castle Books/ Harper Collins, 1995.

It is worth noting—and has been noted by critics—that Barks does not translate Rumi’s poems from the original Persian, and does not consider them to be scholarly translations. Some fans appreciate the spiritual nature of this creative or spiritual “partnership” that spans centuries; some detractors criticize it, pointing out that Bark’s translations are often so generalized that specific Islamic references have been taken out of them to make them more accessible and mystical.

Jen, I loved this post, especially the historical tidbits that walked us through Rumi's path from a young boy to a beloved cultural figure in poetry. I loved learning more about the poet behind the famous lines.